10 March 2026

Besides the usual cacophony, photo-ops and elite confabulations, the World Economic Forum at Davos this year will witness an unprecedented political spectacle – the unveiling of US President Donald Trump’s Board of Peace for Gaza. Encouraged by the UNSC Resolution 2803’s endorsement of Trump’s peace plan for Gaza, Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ seeks a transitional administration in the Palestinian territory, sans the latter’s endorsement or participation, through what looks like a privately-funded elite grouping of Trump’s choosing. While Davos may not yet reveal what kind of ‘political animal’ the Board of Peace will turn out to be, the initiative indicates a shift towards a leader-centric system where multilateralism will be selective and market-style governance will rule the roost, says Professor Swaran Singh in this 16th edition of Asia Watch.

Home image: President Donald Trump addressing a previous version of the WEF

Text page image: Davos decked up for the WEF Annual Meeting 2026

Banner: President Donald Trump exiting Air Force One

This Wednesday, at the Davos World Economic Forum, President Donald Trump arrives with the largest American delegation since this forum began its annual meetings in the early 1970s.

Starting Monday, equally unprecedented is the overall attendance at this year’s forum that includes over 3,000 delegates representing 130 countries, including 64 heads of state or government, over 850 CEOs or Chairs of the world’s top companies or bodies, and a large number of advocacy groups, academicians, celebrities and, of course, media persons.

The show-stopper, of course, will be President Donald Trump’s assertive foreign policy speech about Venezuela, Greenland and tariffs, which is likely to be the highlight of this month’s headlines.

Image: US President Donald Trump and other leaders from West Asia at Sharm El-Sheikh in October 2025

But what portends to be potentially even more game-changing will be his path-breaking engagement in chairing the inaugural meeting of his Board of Peace for Gaza, which promises to forever redefine various global governance indices.

Understandably, Trump’s entourage includes five cabinet secretaries — Marco Rubio (Secretary of State), Scott Bessent (Treasury Secretary), Howard Lutnick (, Commerce Secretary), Chris Wright (Energy Secretary), Jamieson Greer (US Trade Representative) — plus his Special Envoy, Steve Witkoff and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, who has been an active interlocutor on Gaza peace since Trump’s first term in office.

Governing territories eternally: What history tells us

Davos has historically been the site where new global governance ideas are floated before they are formalised, quietly abandoned or marginalised. In the same vein, the theme of WEF 2026 is “A Spirit of Dialogue,” which, however, could be a heroic stretch amidst Trump’s tantrums smashing the existing world order.

Various speculations and insinuations have, accordingly, created a peculiar mix of anticipation, skepticism, and even diplomatic unease about what his Board of Peace may imply.

Historically, the United Nations is not new to governing — or co-governing — territories emerging from conflict. But history also shows a clear pattern: when the UN steps into governance, it does so institutionally and on a strong legal footing, bureaucratically, and under the authority of the Secretary-General, not under the personal leadership of a single state or political figure.

Classic examples include: (a) UNTAET (East Timor, 1999–2002): a full UN transitional administration exercising executive, legislative, and judicial authority, (b) UNMIK (Kosovo, 1998-1999): an interim civil administration pending final status negotiations, (c) UNTAC (Cambodia, 1992–93): oversight of elections, demobilisation, and civil administration, (d) UNTAES (Eastern Slavonia, 1996–98): transitional governance and reintegration.

All these missions shared four defining characteristics: (i) direct UN ownership, through the Secretariat, (ii) Security Council clarity, even when mandates were contested, (iii) assessed or pooled financing, subject to UN oversight, (iv) temporary authority, explicitly aimed at restoring sovereign governance.

President Trump’s Board of Peace departs from every one of these precedents.

Board of Peace – an unprecedented initiative

Trump’s proposed Board of Peace is not a UN transitional administration, nor a peacekeeping mission, nor a trusteeship. It appears instead to be a hybrid construct: politically backed by the United States, but underwritten by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2803, which ‘endorses’ Trump’s peace plan and ‘welcomes’ his Board of Peace “as a transitional administration” in Gaza.

All this remains operationally detached from the UN system.

Image: President Trump with members of his Cabinet

In short, President Trump’s proposed Board of Peace resembles a geopolitical consortium more than an international organisation. Its declared members include President Donald Trump as Chair and Marco Rubio, Steve Witkoff, Jared Kushner, Sir Tony Blair, Marc Rowan, Ajay Banga, and Robert Gabriel as members, while several other heads of state or government and other personalities have also been invited.

But as it stands today makes it, in several ways, unprecedented:

(i) Leader-centric design

Unlike UN missions led by Special Representatives appointed by the Secretary-General, the Board of Peace for Gaza is spearheaded by Trump himself. Remember, on his Social Truth recently, President Donald had declared himself as the Acting President of Venezuela.

In this backdrop, his Board of Peace surely marks a radical departure from multilateral norms, personalising authority in a way that blurs the line between international governance and political entrepreneurship.

(ii) Selective multilateralism

President Trump remains the sole authority to determine the composition of this Board of Peace. The membership in this top-down multilateralism is based on invitation, not representative of any agreed formulae or logic.

Several major stakeholders may remain uninvited, and those invited may oscillate too long. Also, states may join — or refuse — based on their political alignment and financial capacity, not regional balance, or UN voting processes. Former UK prime minister Tony Blair has already distanced himself from this initiative, especially from its USD 1 billion membership fee.

(iii) Market-style governance logic

The influence of members appears linked to contribution levels, not assessed in terms of responsibilities. This introduces a pay-to-participate logic of market-driven oligopoly that not only remains alien but contradicts all traditional UN peace operations. Nothing is clear about members’ rights and responsibilities.

The question of legal mandate

Much hinges on references to Security Council endorsement in UNSC Res 2803. But it remains open to interpretation as to what that UNSC endorsement implies or does not imply. Even if this UNSC resolution welcomes the initiative, that alone does not imply mandating a governing authority comparable to UNTAET, UNMIK, UNTAC or UNTAES.

The most glaring legal ambiguities includes lack of clear delegation of sovereign authority. Legally speaking, endorsement is not the same as authorisation. Unless the UN Security Council explicitly transfers administrative powers, the Board operates in a legal grey zone to say the least.

Sourcing its mandate to UN Charter remains unclear. Will the Board be acting under Chapter VI (peaceful settlement) or Chapter VII (enforcement)? That distinction matters enormously for legitimacy and compliance purposes.

According to the Board’s draft charter, each permanent seat on it has a price tag of USD 1 billion contribution, but there is complete silence about financial and overall accountability. There is little clarity on reporting lines: Who audits the Board? Who investigates misconduct? Who answers to whom?

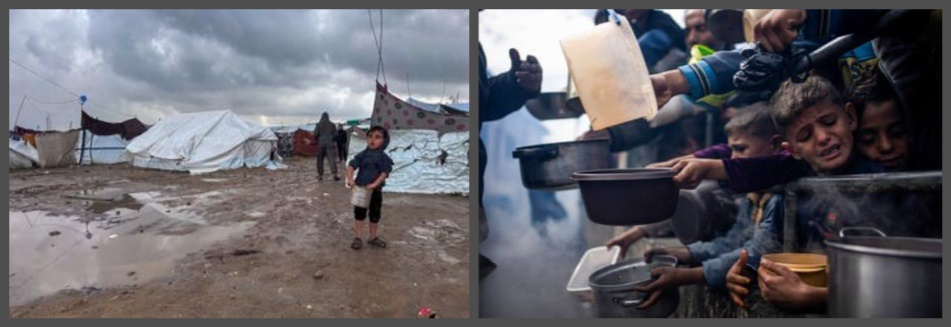

Image: A boy at the relief camp in Jabalya, Northern Gaza (left); and kids reach out for food in another Gaza camp (right)

Most important is the continuing ambiguity on Palestinian consent in constituting it. All previous UN administrations were at least nominally grounded in host-territory consent. The Board’s relationship with Palestinian political representation remains undefined.

The Board remains potentially vulnerable to insinuations of members buying influence and proximity to President Trump instead of financing peace in war-torn Palestine. Its informally-proposed financing model remains unprecedented.

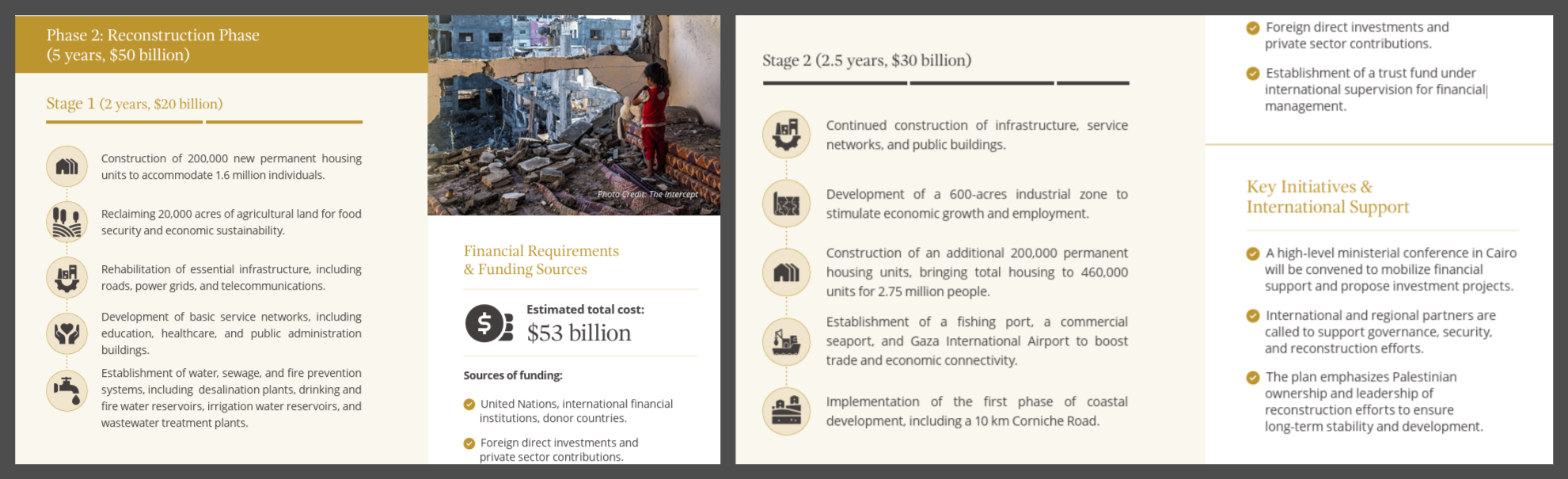

Unlike all UN missions funded through assessed contributions, Trump’s Board of Peace funding appears designed around (a) voluntary state contributions, (b) large one-time financial commitments, and (c) potential private or philanthropic funding.

This raises several misleading red herrings. If big donors will shape policy, neutrality becomes implausible. Without UN oversight mechanisms, financial governance risks reputational and legal vulnerabilities.

Proposed bodies — such as an 11-member Gaza Executive Board or an International Stabilisation Force — may each require separate funding streams, multiplying coordination and accounting problems. Reconstruction and stabilisation are multi-decade tasks, and such voluntary enthusiasm may dry quickly.

In effect, President Trump’s Board of Peace risks privatising peace governance, with all the distortions that the above examinations imply.

Silence and skepticism of the stakeholders

Among major powers, neither Russia nor China has embraced the initiative enthusiastically. Both of them abstained in UNSC Res 2803. While China’s UN Ambassador Fu Cong called the text “vague and unclear,” Russian Ambassador Vasily Nebenzia compared it to “colonial practices,” calling it reminiscent of the British Mandate system.

Historically, both Russia and China have resisted governance mechanisms perceived as US-driven or norm-breaking, particularly when they weaken the already eroding UN institutional authority. Their cautious silence suggests a strategy of watchful waiting, rather than endorsing it.

Regional response has also been mixed and muted. Some Arab states appear open to participation, seeing a chance to shape outcomes. Others fear legitimising an arrangement that sidelines Palestinian agency. Iran views the initiative through the lens of US regional pressure, interpreting it as part of a broader containment strategy.

Indeed, continued US-Iran tensions — and protests within Iran — intersect indirectly with the potential distractions for the everyday functioning of this Board of Peace. Tehran’s suspicion of US-led regional restructuring may harden its opposition, while Washington may view the Board as a means to stabilise one front of an otherwise volatile region.

India has also been invited to join this Board of Peace. There is no denying that India has enormous goodwill in this turmoil-ridden West Asia. Since September 2021, India has been part of President Joe Biden’s I2U2 (India, Israel, UAE, US) quad. India has supported peace and reconstruction in principle and stands broadly in support of President Trump’s 20-point peace plan.

But India has had an enduring discomfort with any extra-UN governance experiments, particularly those that personalise authority and blur multilateral norms.

India’s power-packed presence at Davos with four Union Ministers — Ashwini Vaishnav, Shivraj Singh Chauhan, Pralhad Joshi and K Rammohan Naidu — and six Chief Ministers, plus over 100 businessmen and CEOs, will face the dilemma of avoiding or engaging with Board of Peace-related commentaries.

They must tread carefully in endorsing this leader-centric international regime in-the-making. In this case, choosing subtle diplomacy and public silence will be a pragmatic strategy.

What to expect from the Davos Board Meeting?

In the midst of such urgency and uncertainties, several heads of state and government invited by President Trump to join the Board had not yet responded, thus creating ambiguity about whether such a meeting will actually take place this week.

Yet, if President Trump manages to hurriedly convene a meeting of selected invitees, this largely symbolic meeting will still be pregnant with possibilities. The key question is not in what shape and size the Board of Peace meets, but what kind of political animal it reveals itself to be.

If a first meeting of President Trump’s Board of Peace does occur this week, the least expected outcomes are likely to include several announcements (not decisions), donor signalling (not pledges), wish lists (not operational plans), and carefully staged optics (with little legal clarity).

President Trump’s grandstanding will once again be ambiguous about its substance. The Board of Peace thus risks becoming a headline without a horizon in sight.

As of today, the Board seems nothing more than a grand initiative in-the-making. Its membership itself remains unclear, with several nations staying out of it, not being invited or not responding to President Trump’s invites. Others are still in the process of receiving invitations.

About three dozen names have been in circulation, representing a whole range of leaders and personalities.

The real test will not be the Board meeting itself, but whether its members are able to initiate some concrete decisions like creation of a permanent secretariat to operationalise leaders’ grandstanding, materialise funding pledges and formally integrate the Board with the UN system instead of making it further Leader-centric.

Innovation or precedent-breaking gamble?

President Trump’s Board of Peace for Gaza may evolve into a meaningful coordination mechanism — or fade into diplomatic footnotes. What makes it historically significant is not its effectiveness — which is still unproven — but its challenge to how international governance is imagined.

If Davos marks the birth of this precedent-breaking initiative, it will be a birth shrouded in ambiguity. And, in international politics, ambiguity is rarely a stable foundation for peace.

Unlike established multilateral bodies, the Board of Peace has no publicly-released founding statute ratified through standard UN processes, no confirmed permanent secretariat, and no universally acknowledged membership list.

What exists instead is a cluster of announcements, draft charters circulated informally, and selective briefings suggesting that Davos may serve less as a legal founding moment and more as a performative launch — a signalling exercise aimed at donors, allies, and critics alike.

Is the world already getting comfortable with this game-changing Trumpspeak!

Follow us on WhatsApp

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X @vudmedia

Follow us on Substack