22 January 2026

India speaks loudly of growth and progress, yet often falls silent when confronted with ecological truth. The passing of Madhav Gadgil, one of the country’s most influential environmental thinkers, exposed this uneasy silence. His ideas—rooted in scientific rigour, democratic participation and ecological limits—were neither anti-development nor nostalgic, but deeply unsettling to a system driven by speed, centralisation and extraction. Through the fate of the Gadgil Report and the parallel tragedy of G. D. Agarwal, a troubling pattern emerges: ecological conscience is sidelined, delayed, or exhausted when it challenges power and profit. The neglect of such voices is not accidental; it reflects a deeper discomfort with restraint and dissent. The choice India faces is stark—continue treating nature as expendable, or move toward a biocentric understanding where democracy, justice, and survival are inseparable.

India is not a quiet country. It speaks loudly—about growth, development and global ambition. Yet when Madhav Gadgil, one of the country’s most important ecological thinkers, passed away, the response from the state and from much of the mainstream national media was marked by indifference.

There was no serious public reflection, no sustained discussion and no visible attempt to engage with the ideas he spent a lifetime developing.

That indifference was not absolute, but it was telling. His death was, of course, reported by mainstream national media and reflected on by independent journalists, environmental scholars, and smaller digital platforms, though much of this commentary remained within specialised or academic spheres.

He was cremated with state honours, and the Government of Kerala issued public condolences. Yet beyond these formal gestures, there was little sustained governmental or national media engagement with his ideas or legacy. While many in the environmental community paid tributes, dominant media institutions failed to consistently foreground his passing as a moment for deeper public reflection.

Such apathy is rarely accidental. Thinkers like Gadgil are often sidelined because they speak inconvenient truths. Their arguments are rooted in public interest, ecological justice and long-term survival, but they sit uneasily with the priorities of those in power and with corporate models that view land, forests and rivers primarily as resources to be exploited.

Gadgil spoke of limits, decentralisation and the rights of local communities—ideas that challenge both political authority and profit-driven development.

When mainstream platforms choose not to engage with such voices, it reflects a deeper discomfort with dissenting knowledge. We live in a time that celebrates speed and spectacle, but has little patience for caution or critique.

In this environment, ignoring a thinker becomes easier than confronting what he represents.

Gadgil’s passing, therefore, should not be seen merely as a personal loss or an academic moment. It is a civilisational signal. It asks whether we are willing to listen only to voices that flatter power, or whether we still have space for those who speak for the land, for ordinary people and for futures that cannot be measured in quarterly profits or election cycles.

Who was Madhav Gadgil, really?

It is easy, after a public intellectual passes away, to reduce a life to positions held and committees chaired. Madhav Gadgil, of course, had many such credentials—scientist, ecologist, institution builder, and academic. But to remember him only through titles would be to miss the essence of who he was and why his work mattered.

At heart, Gadgil was a thinker who refused to separate knowledge from responsibility. He believed that science was not meant to sit comfortably within conference halls or government files, but to speak to society at large—especially to those who are most affected by policy decisions. His work consistently tried to bridge the gap between academic knowledge and lived reality.

It is also important to say clearly what Gadgil was NOT. He was not anti-development, as he was often portrayed. He understood the needs of a growing country and the aspirations of its people.

What he opposed was blind development—projects conceived without listening to local communities, without understanding ecological limits, and without considering long-term consequences. To him, development without ecological wisdom was not progress but recklessness.

What set Gadgil apart was his insistence that knowledge must serve people, not power. He questioned the idea that decisions about land, forests, rivers and livelihoods should be taken far away from those who live with their consequences. His faith lay in decentralisation, public participation, and democratic decision-making—ideas that are frequently spoken of, but rarely practised.

In an age where expertise is often used to justify authority, Gadgil used expertise to challenge it. That, perhaps more than anything else, explains why his ideas were uncomfortable for many and why his voice, though respected in academic circles, was so often sidelined in the corridors of power.

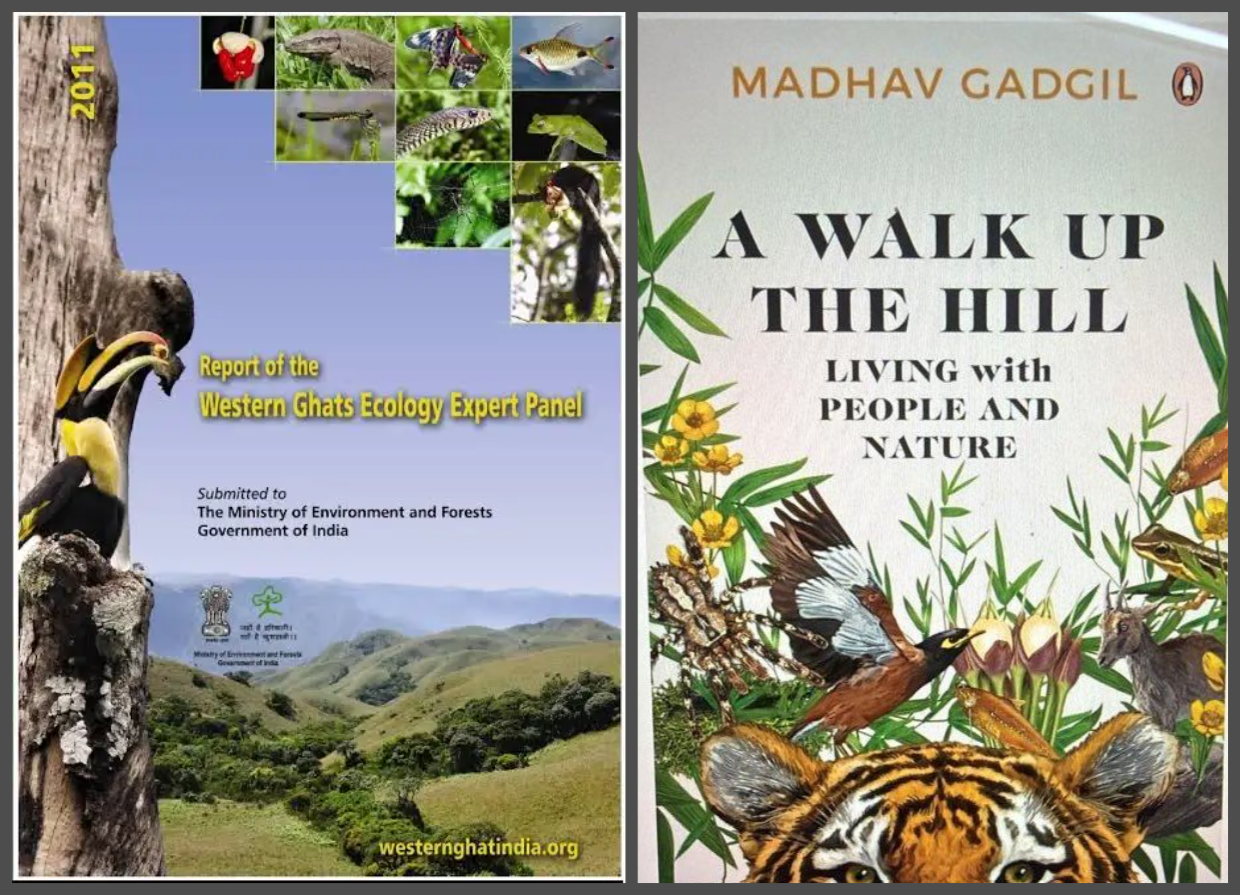

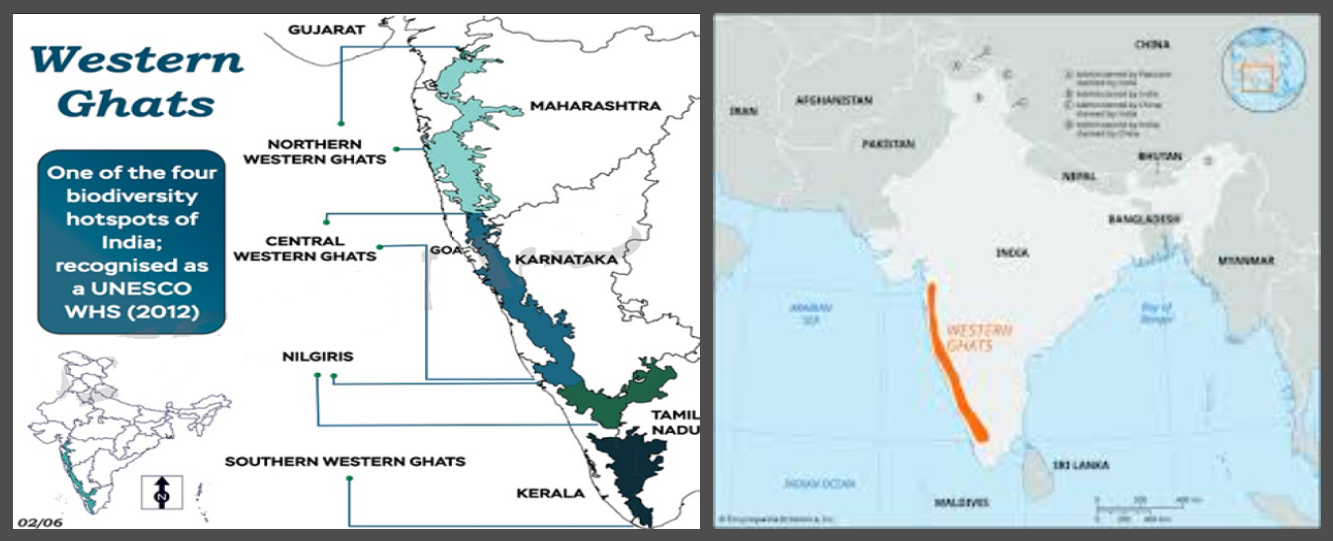

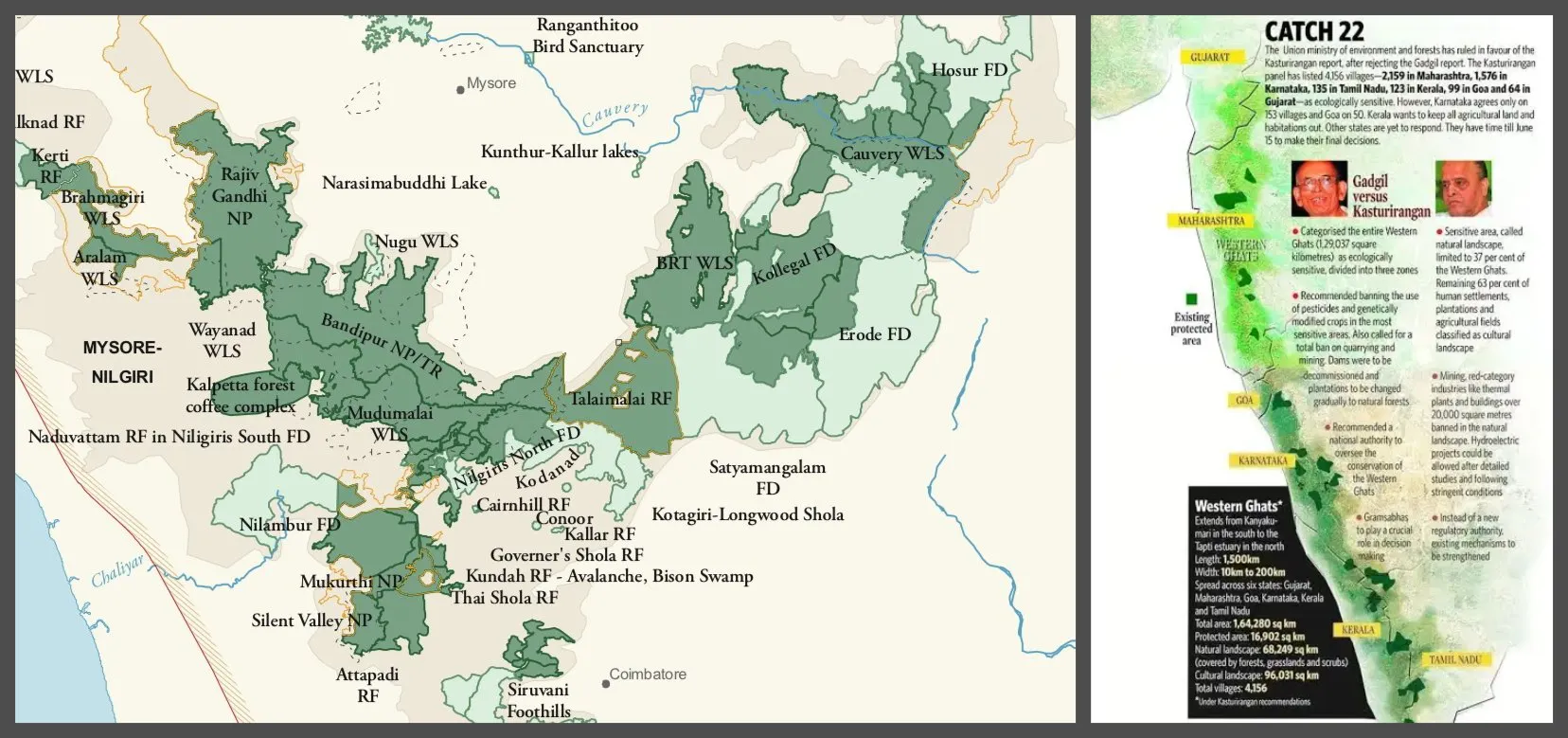

The Gadgil Report and the crime of ignoring science

The most visible and contested expression of Madhav Gadgil’s thinking came through the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel, commonly known as the Gadgil Committee. Constituted to study one of the most fragile and biodiverse regions in the country, the panel produced a report that was rigorous, detailed and deeply uncomfortable for those accustomed to top-down decision-making.

What the report offered was not an abstract environmental ideal. It proposed a democratic and decentralised framework, where ecological protection went hand in hand with people’s participation. Instead of blanket bans or distant controls, it argued for graded ecological sensitivity, local consent, and the involvement of panchayats and local institutions. In simple terms, it trusted people who live in the Western Ghats to be partners in conservation, not obstacles to development.

This approach stood apart from the usual model where decisions are taken in capital cities and implemented on the ground with little regard for local realities. The Gadgil Report recognised that environmental protection cannot be enforced through force or fear, but must grow from shared responsibility and local knowledge. It was, in many ways, a people-first environmental document.

Yet the fate of the report tells its own story. Instead of engaging with its scientific findings, successive governments chose to dilute, delay, or quietly set it aside. The science was never convincingly challenged. The data was never decisively disproved. What was avoided was the report’s central idea—that development must accept limits, and that power over natural resources cannot remain concentrated in the hands of a few.

By sidelining the report without honest debate, the state committed a quieter but more serious offence: the dismissal of science through silence. This was not rejection after scrutiny, but evasion without accountability. In doing so, an opportunity was lost—not only to protect a vital ecological region, but to demonstrate that policy in India could be guided by knowledge, democracy and ecological sense rather than expediency.

Environmentalism as dissent, not decoration

In India, environmentalism is rarely opposed openly. It is welcomed as long as it remains symbolic. Tree-planting drives, glossy sustainability reports, and carefully managed green images are encouraged.

What meets resistance is environmentalism that demands restraint, questions priorities, or asks who truly benefits from development. When ecology turns into dissent rather than decoration, unease follows.

Madhav Gadgil belonged to this inconvenient tradition. He did not speak the language of cosmetic greening. He spoke of limits—limits to mining, construction, and unchecked extraction. In a political culture that equates development with speed and expansion, such arguments are quickly labelled obstructionist. Yet Gadgil’s case rested not on ideology, but on ecology and long-term survival.

Across governments, there has been a clear preference for green rhetoric over real ecological restraint. Environmental concerns appear in speeches, but rarely shape policy in meaningful ways. The focus remains on managing damage after it occurs, not on preventing it.

Gadgil challenged this approach by asking a simple but unsettling question: should some kinds of development not happen at all?

That question goes to the heart of power. It forces a choice between immediate economic gain and long-term ecological stability. It asks for accountability from those who decide today but will not face the consequences tomorrow. Gadgil’s refusal to soften this question explains why his ideas were praised in theory, but sidelined in practice.

The state vs the scientist: A quiet hostility

The Indian state is rarely hostile to science in the open. It often celebrates scientists—so long as they stay within acceptable limits. Expertise is welcomed when it supports existing priorities or justifies decisions already taken. Problems arise when science begins to question direction, costs, or consequences.

A familiar pattern follows. Scientists are valued when they are compliant and used to fine-tune policy. But when the same expertise raises uncomfortable questions—about ecological limits or social impact—it is gradually pushed aside. This sidelining is quiet. It happens through delay, dilution and silence, not confrontation.

Madhav Gadgil’s career reflected this pattern. He was consulted, respected and appointed. Yet when his work challenged the dominant development narrative, official engagement slowly faded. His arguments were not defeated with better science; they were simply allowed to disappear from public discussion.

This is how independent expertise is often managed in India—not by rejecting it outright, but by containing it. Committees are formed, reports submitted, acknowledgements made. Over time, the inconvenient ideas are dropped, while the expert remains.

The message this sends is clear: speak carefully, question less, and do not go too far. Gadgil refused to accept this role. He believed that a scientist’s duty in a democracy is not only to advise power, but to challenge it when evidence demands. That conviction kept him at a quiet, uneasy distance from the state.

Anthropocentrism as the ideology of power

Many of India’s environmental conflicts rest on a quiet assumption: that nature exists mainly for human use. Forests become timber, rivers become water supply, and mountains become mineral reserves. This way of thinking places human ambition—and increasingly market logic—at the centre of all decisions. Everything else is expected to adjust.

Madhav Gadgil challenged this worldview without slogans or rhetoric. He argued that human societies are part of ecological systems, not their masters. His insistence on ecological limits reflected a biocentric view—one that recognises the value of all life, not only what serves immediate human needs.

Anthropocentrism fits easily with extraction-led development. It justifies clearing forests, damming rivers and reshaping landscapes in the name of growth, often ignoring downstream impacts. Biocentrism demands humility. It recognises that ecosystems have limits, and that crossing them invites consequences that technology cannot always fix.

Gadgil did not oppose human needs. He argued that respecting ecological limits is essential for human survival itself. By grounding policy in ecological reality, he challenged the belief that development can continue endlessly without cost.

In questioning anthropocentrism, Gadgil was doing more than making an environmental case. He was exposing an ideology of power—one that values immediate gains over long-term balance, and control over coexistence.

That deeper challenge explains why his ideas remain relevant and unsettling. Thus, Gadgil was not dangerous because he was radical. He was dangerous because he was reasonable. He questioned power quietly, by asking who has the right to decide the fate of land, forests and livelihoods.

Taken together, these ideas challenged the foundations of the status quo. They disrupted a system where power flows downward, and profit flows upward. By insisting on local voice and ecological sense, Gadgil exposed the fragility of that system—and made himself easy to sideline.

The parallel tragedy: G. D. Agarwal

The silence that followed Madhav Gadgil’s passing is not without precedent. A few years earlier, the country witnessed another troubling episode—one that revealed, in a far more visible and painful way, how ecological conscience is treated when it refuses to yield.

G. D. Agarwal, a former IIT professor and respected environmental scholar, was forced into an act of extreme protest to defend India’s rivers.

Unable to secure meaningful attention through reports, appeals, or dialogue, he chose the last form of dissent available to him: a fast unto death. Even then, his demands were met largely with indifference and procedural evasions. He died not because his arguments lacked merit, but because they were inconvenient.

Image: Madhav Gadgil (left) and G.D. Agarwal (right)

The contrast between the two men is striking, yet deeply connected. Gadgil was ignored. Agarwal was allowed to starve. One was sidelined quietly, the other visibly, but the underlying message was the same. When ecological concerns challenge entrenched interests and dominant development models, they are not engaged with—they are exhausted, delayed, or worn down.

Both men believed in reason, science and democratic persuasion. Neither sought confrontation for its own sake. Yet both were pushed to the margins by a system that treats ecology as expendable and environmental limits as negotiable. In their different ways, they paid the price for refusing to accept that destruction is the inevitable cost of progress.

Together, their stories form a grim record of how environmental dissent is handled in contemporary India. Whether through silence or suffering, the outcome is similar: the erosion of ecological conscience and the normalisation of loss. Remembering them side by side is not an act of sentiment—it is an act of reckoning.

What kind of nation forces its conscience to die alone?

What does it say about a society when those who speak for rivers, forests, and fragile landscapes are left unheard? When scientific warning meets indifference, and moral insistence meets delay, the problem goes beyond policy. It reaches the level of conscience.

Is progress to be measured only in roads built and projects cleared, while voices that warn of irreversible loss are pushed aside?

Image: The Loharinag-Pala hydroelectric project on the Bhagirathi River, shut down by the Uttarakhand government after Prof G.D. Agarwal's fast of over 111 days seeking to restore the 'aviral' or uninterrupted flow of the Ganges

Can a nation speak confidently about its future while treating ecological concern as an inconvenience? These are not merely political questions. They are moral ones.

Every society has its sentinels—people who watch carefully and speak when danger approaches. Ecologists like Madhav Gadgil and G. D. Agarwal played that role out of responsibility, not ambition. Their marginalisation suggests a growing impatience with warning and a discomfort with restraint.

Carrying the flame forward

Public remembrance is easy. Statements are made and tributes written. But remembrance without action soon rings hollow. In Madhav Gadgil’s case, praise after years of disregard risks becoming an empty ritual.

The real tribute lies in acting on his ideas. That begins with reviving ecological federalism—placing environmental decisions closer to the ground, guided by local knowledge and democratic participation. For Gadgil, this was not a theory, but a practical model of governance.

It also means trusting science over slogans. Not selective science used to defend decisions already taken, but independent science that raises difficult questions. Listening to science requires accepting that some projects should not proceed, even if that slows development.

Image: A glimpse of the eco-sensitive Western Ghats, which Madhav Gadgil strived to safeguard

Above all, it calls for choosing restraint over speed. Gadgil believed that development judged only by pace often ignores what it destroys. Restraint, to him, was not weakness but wisdom and ecological stability, the foundation of lasting progress.

Carrying the flame forward is not about invoking Gadgil’s name. It is about accepting the discomfort his ideas create and allowing them to shape decisions.

Ideas do not disappear. They return. Silence may delay a reckoning, but it does not remove the questions Gadgil left behind—it only postpones the cost of ignoring them.

Follow us on WhatsApp

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on X @vudmedia

Follow us on Substack