22 December 2025

Part - II

Long before Indians flocked to the western hemisphere in huge numbers in pursuit of the ‘American dream,’ and even longer before India and US, the world two largest democracies (one by size and the other by population, decided to pursue a ‘strategic partnership’ after decades of ‘estrangement,’ the two societies were already in touch – through intellectual and spiritual exchanges. In this second edition of Glimpses from an Eastern Window, Professor Shantanu Chakrabarti takes us through the history of these connections.

The sharp nosedive in India-US relations since the recent announcement of the new tariff rates for India by US President Donald Trump has attracted global media attention. Last week, President Trump imposed tariffs totaling 50 percent on India, including a 25 percent levy as a penalty for India’s purchase of Russian oil.

In an interview with Bloomberg TV, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has warned that Washington could increase ‘secondary tariffs’ against India if the Trump-Putin meeting in Alaska, scheduled for August 15, 2025, does not yield satisfactory results.

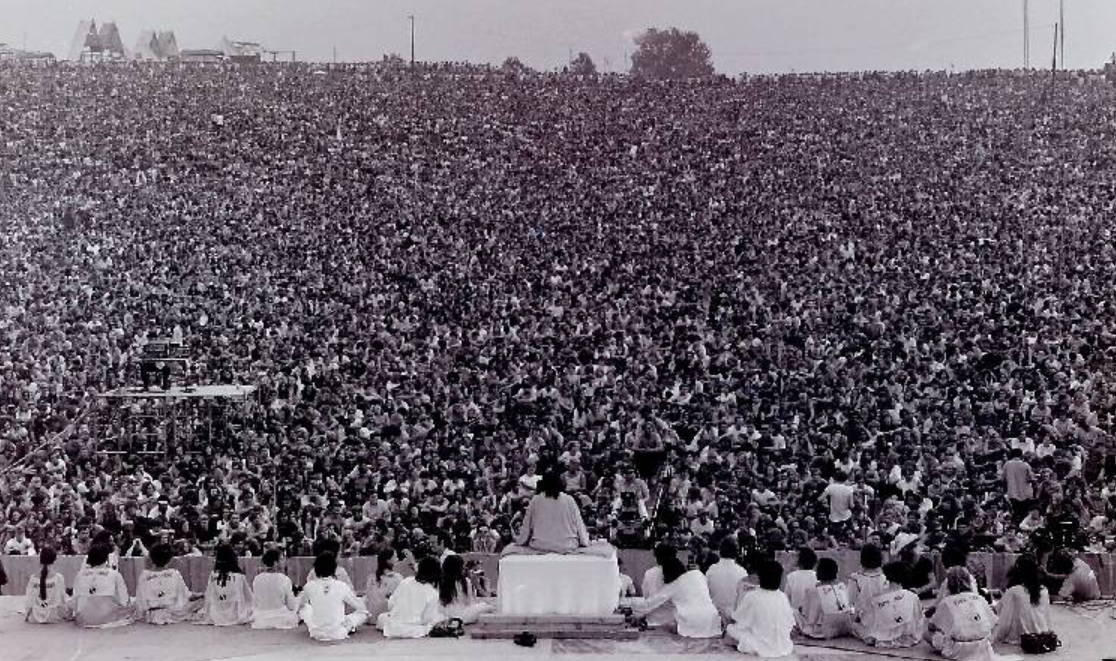

Image: The first World’s Parliament of Religion held at in Chicago in 1893. Photo courtesy: Vivekavani

Image: The first World’s Parliament of Religion held at in Chicago in 1893. Photo courtesy: Vivekavani

“We've put secondary tariffs on Indians for buying Russian oil. And I could see, if things don’t go well, then sanctions or secondary tariffs could go up,” Bessent is quoted as saying in this interview.

The deterioration in relations between the world’s two largest democracies has generated several critical assessments, blaming both the American and Indian leadership. Veteran American analyst Ashley J. Tellis, for instance, has initiated a debate by bluntly referring to India as a ‘delusional power’ in his recent Foreign Affairs article.

Observers like Nirupama Rao, who has served as India’s Foreign Secretary, and a few others have tried to counter Tellis’s contention with Rao describing India as a ‘liminal power’ and a firm believer in multilateralism. Despite such spirited defence, many sections of the global media have been critical about India’s grand strategy, with even prominent voices within India also echoing such views.

For instance, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, in a commentary earlier this year, has referred to India’s conception about its place in the world as a “delusion of relevance.”

It must be admitted that the India-US relations have never been smooth and, in spite of convergence of certain interests and sharing of some core values, as Dennis Kux pointed out in 1992, both have remained “estranged democracies.” The relationship, Rudra Chaudhuri further points out, has been “forged in crisis.”

The truth is, India lost its strategic importance to the United States as the Second World War ended, and regional geopolitics began to evolve and was increasingly shaped by the Cold War dynamics.

Under the circumstances, as has been shown by scholars like Rakesh Ankit, as to how official American attitude, particularly within the strategic circles, hardened against India. Eventually, the situation opened the prospects for a long-term American relationship with Pakistan’s strategic and elite community.

One could, however, further argue that the patterns of such an ‘on-off’ relationship have had historical origins with early intellectual connections reflecting similar trends. Realism and contemporary strategic aspects do play important roles in forging the relationship.

However, mutual perceptions are also shaped by historically-derived memories and cultural tropes which continue to directly or imperceptibly influence the decision makers and institutions in both countries.

Hence, a brief recollection of the early intellectual contact process may not be out of place and yield crucial clues about the present trends.

The earliest connections

Swami Vivekananda’s (1863-1902) visits to the United States and his celebratory speech at the 1893 World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago along with the efforts of other spiritual leaders like Paramhansa Yogananda (1893-1952) and Swami Abhedananda (1866-1939), whose visits to America had generated an interest about India and its spirituality.

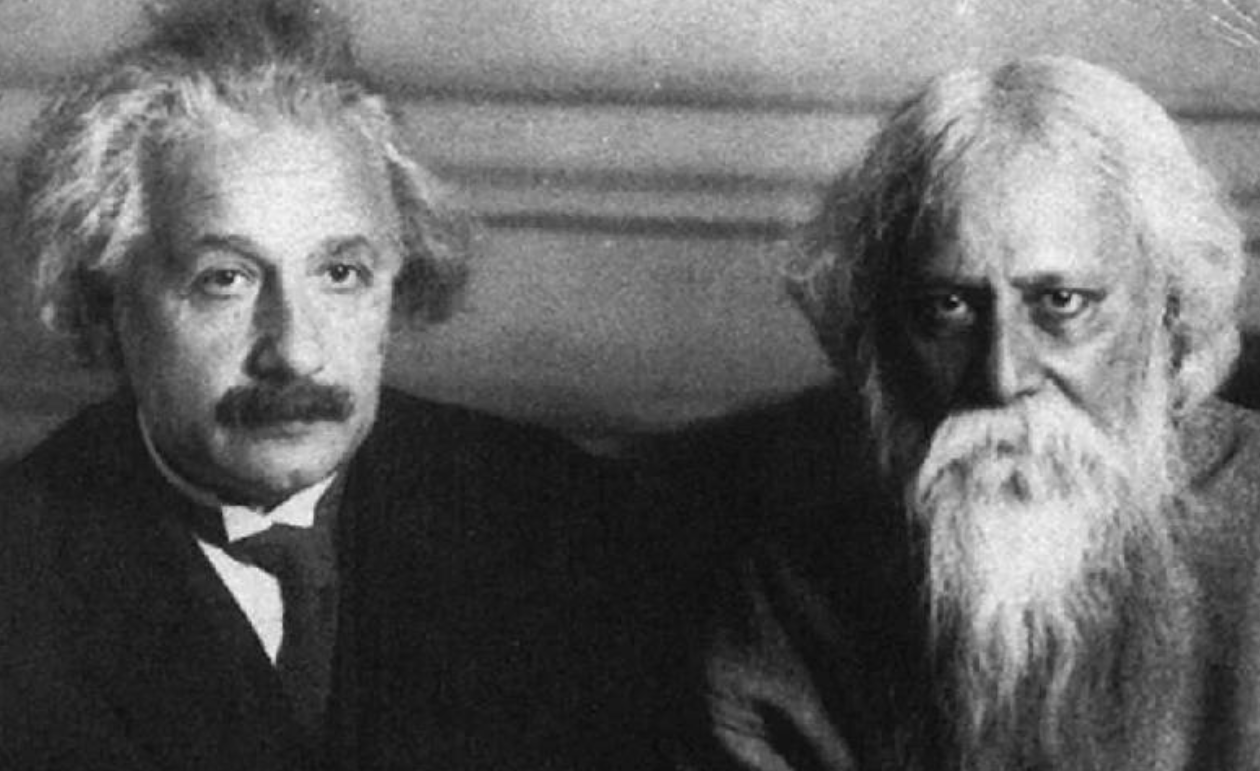

Image: Rabindranath Tagore with Albert Einstein. Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Image: Rabindranath Tagore with Albert Einstein. Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Initial encounters with the Orient produced a combination of incredulity and wonder, leading to different proportions of appreciation and revulsion, depending upon the subjective analyses by observers.

The celebrated American author Mark Twain’s (1835-1910) observations, for instance, upon his arrival in India for the first time in 1896 and after disembarking at Bombay were:

“This is indeed India; the land of dreams and romance, of fabulous wealth and fabulous poverty, of splendour and rags, of palaces and hovels, of famine and pestilence, of genii and giants and Aladdin lamps, of tigers and elephants, the cobra and the jungle, the country of a hundred nations and a hundred tongues, of a thousand religions and two million gods.”

All his ruminations and diatribes about India, even if based on his own experience, was also influenced helped with his dependence on British texts and writings. Interestingly, Twain, during his visit to Varanasi, confesses his fascination for the contemporary renowned ascetic Swami Bhaskarananda Saraswati (1833-1899).

Equating him along with the Taj Mahal as two living Gods in India, Twain comments:

“I believe I have seen most of the greater and lesser wonders of the world, but I do not remember that any of them interested me so overwhelmingly as did that pair of gods…What is the Taj as a marvel, a spectacle, and an uplifting and an overpowering wonder, compared with a living, breathing, speaking personage whom several millions of human beings devoutly and sincerely and unquestioningly believe to be a god, and humbly and gratefully worship as a god?”

“I believe I have seen most of the greater and lesser wonders of the world, but I do not remember that any of them interested me so overwhelmingly as did that pair of gods…What is the Taj as a marvel, a spectacle, and an uplifting and an overpowering wonder, compared with a living, breathing, speaking personage whom several millions of human beings devoutly and sincerely and unquestioningly believe to be a god, and humbly and gratefully worship as a god?”

The early twentieth century also would witness some noted encounters. One could refer, in this connection, to the huge controversy generated in the public sphere over the publication of American author Katherine Mayo’s (1867-1940) bestseller book Mother India, published in 1922.

Mayo made critical observations about India’s poverty and perceived social ills (particularly the condition of Indian women). She was also critical of the Indian national leadership, including Mahatma Gandhi, for not sufficiently and adequately addressing such issues before demanding political freedom, which generated a huge controversy both within India and abroad.

Much of this debate, ultimately, centred upon India’s image, or brand value, in today’s parlance.

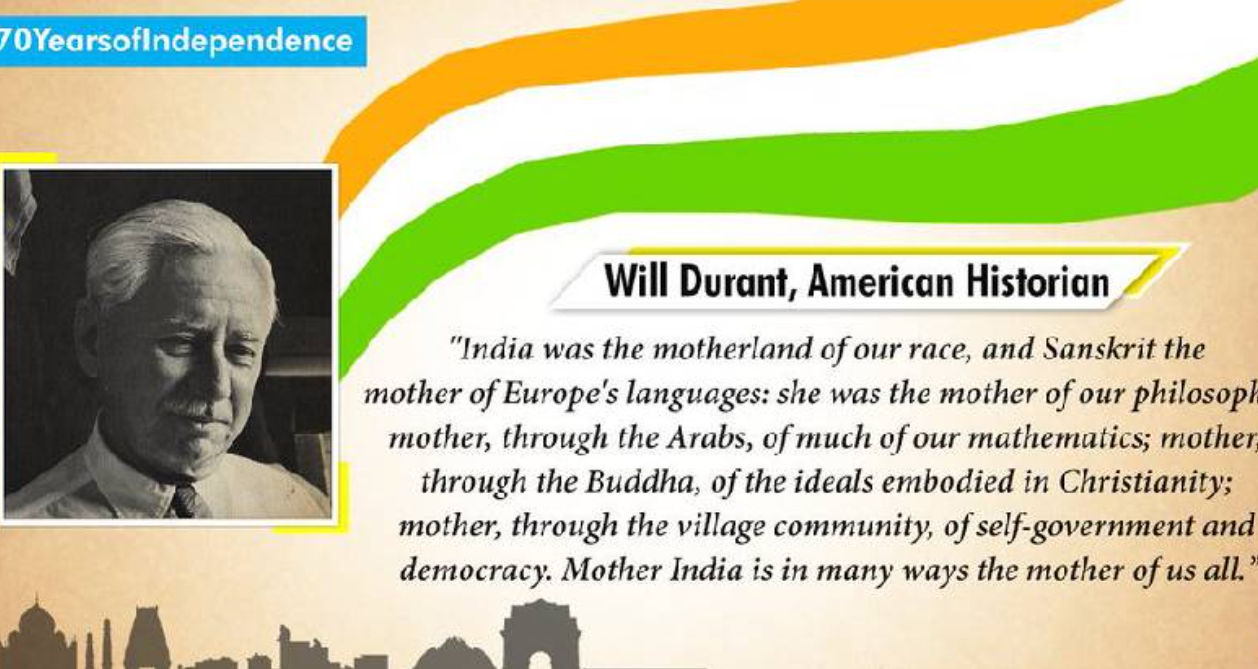

The renowned American philosopher Will Durant (1885-1981) also made some critical observations on Mayo’s Mother India in his own book The case for India (1930) based on his own travels in India during the 1920s. Durant remarked that, “every civilization has its faults, and only the most unfair mind would present a list of the faults as a description of the civilization.”

He concluded by writing, “Mother India is, in many ways, the mother of us all.”

On the Indian side, intellectual voices like Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), who abhorred the idea of India borrowing and adapting Western concepts like modern nationalism, would adopt a critical note when confronted with Western notions of India’s cultural and social aberrations.

During his tour of the United States of America in 1916-1917, Tagore, when asked about Indian racial problems and caste discrimination, commented in a lecture:

“Many people in this country ask me what is happening as to the caste distinctions in India. But when this question is asked of me, it is usually done with a superior air. And I feel tempted to put the same question to our American critics with a slight modification, ‘What have you done with the Red Indian and the Negro?’ For you have not gotten over your attitude of caste toward them. You have used violent methods to keep aloof from other races, but until you have solved the question here in America, you have no right to question India.”

The Indian nationalist leader Lala Lajpat Rai (1865-1928) also came out with his book The United States of America: A Hindu’s impressions and a study in 1916, based on his travel experiences and interactions in that country. In his book, Rai remarked:

“Of India, Americans generally know very little; perhaps not more than what they read in Kipling’s books or in the writings of their own missionaries… My readers would laugh if I were to recount the stories that I know of the ignorance of even Englishmen about the geography and history of India.” Rai insisted that the onus of removing this perceptive lacuna was, of course, on the immigrant Indians, as Lajpat Rai argues, “Here again, the Indians are responsible for this ignorance and if they and their country suffer thereby in the estimation of the world, the fault is theirs.”

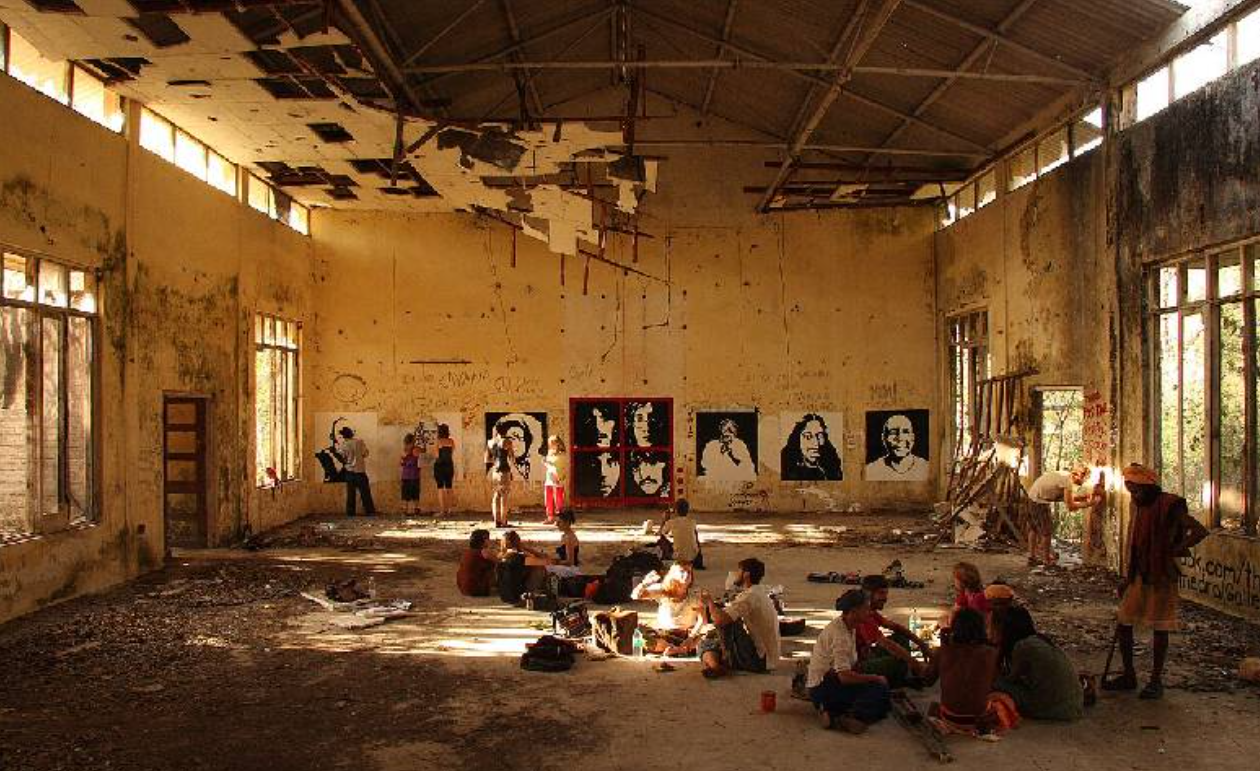

Image: The Satsang Hall of the abandoned Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Ashram in Rishikesh, at the start of revival as the Beatles Cathedral Gallery in 2012. Photo courtesy: Guy P. Atinkson

Image: The Satsang Hall of the abandoned Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Ashram in Rishikesh, at the start of revival as the Beatles Cathedral Gallery in 2012. Photo courtesy: Guy P. Atinkson

Attempts to remove mutual perceptions continued even after 1947. There were concerns that courses about various civilisations were either not being taught in American campuses or were being taught on improvised basis depending upon the interests of particular instructors.

To solve the problem, the Office of Education under the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare initiated a project to prepare a quality syllabus of lecture outlines and readings in 1964-1965. This resulted in a compilation titled “Lectures on Indian Civilization” being published in 1970.

This was projected as a “composite course that takes India’s civilization and traces unity of and relationships between the literary, political, religious, etc., parts. The advantage of the ‘civilisation’ approach is that it allows the student to explore another total way of thinking, and perhaps to acquire a deeper understanding of Indian society as a whole.”

The Indian influence was also evident in the realm of spirituality, ranging from Yoga teaching schools, spiritual centres. These resulted in cultural ventures through the Hippie movement, Osho Rajneesh cult, and the Beatles' engagement with their version of Indian spirituality.

Americanism entered into India, in spite of occasional blocks (for instance, the banning of Coca Cola between 1977 and 1992), and surviving traditions of intellectual Leftist and Nationalist sentiments within the Indian political ecosystem. Over time, India’s intellectual and academic engagement with the US has also enhanced.

Nonetheless, the intellectual caution and wariness of each other, based upon the historically inherited palimpsest, have restrained a more sustained and vigorous engagement leading to institutional connectivity.

This is unlikely to undergo any major shifts in the near future.